When you marvel at the vibrant glow of a neon sign, the precise beam of a laser, or even the subtle shimmer of a firefly, you're witnessing an intricate atomic dance driven by three fundamental principles: Excitation, Ionization, and Photon Emission. These aren't just abstract physics concepts; they're the invisible choreography that powers nearly every form of light we encounter, turning raw energy into the visual spectacle of our world. It's a story of electrons gaining energy, moving to new states, and then releasing that energy as light.

At a Glance: The Atomic Light Show

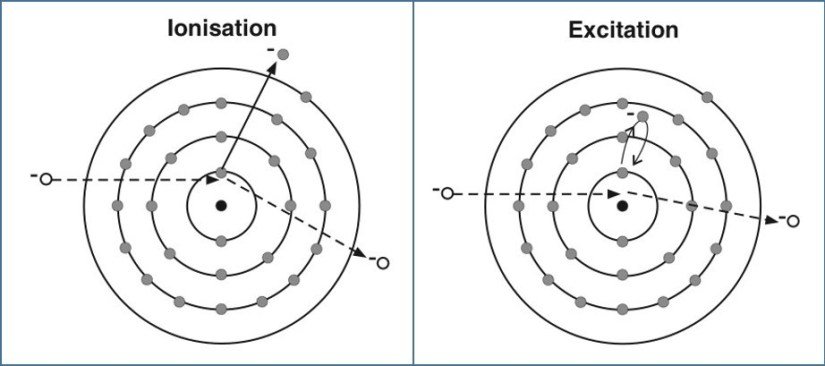

- Excitation: Think of an electron getting a temporary "energy boost," jumping to a higher energy level within its atom, like climbing a stair. The atom is now "excited."

- Ionization: Imagine an electron getting so much energy that it breaks free entirely from its atom, leaving behind a positively charged "ion." This is a permanent change for that electron.

- Photon Emission: When an excited electron falls back to a lower energy level, it releases the excess energy as a tiny packet of light – a photon. The color of that light depends on the size of the energy jump.

- The Link: Excitation is often the precursor to photon emission. Ionization can lead to further excitation or create new atomic environments for light production, especially in plasmas.

- Why It Matters: These processes explain everything from how your TV screen works to the mesmerizing glow of the aurora borealis, and even how scientists analyze the composition of distant stars.

The Atomic Energy Ladder: What is Excitation?

At its core, an atom is a central nucleus orbited by electrons, each occupying specific "energy levels" or shells. Think of these levels like rungs on a ladder: electrons prefer to stay on the lowest available rungs, known as the "ground state." But what happens when an electron gets a jolt of energy?

Excitation is the process where an electron absorbs energy and, as a result, temporarily leaps to a higher energy level within the same atom or molecule. It hasn't left the atom; it's just moved up the internal "energy ladder." This can happen in several ways:

- Photon Absorption: An electron can absorb a photon (a particle of light) that has precisely the right amount of energy to make the jump to a specific higher level. If the photon's energy doesn't match a valid jump, it passes right through.

- Particle Collisions: When atoms or molecules collide with high-energy particles (like other electrons or ions), kinetic energy can be transferred to an electron, boosting it to a higher state. This is common in gases subjected to electric currents.

- Electromagnetic Fields: Exposure to strong electric or magnetic fields can also provide the necessary energy for electrons to become excited.

Once excited, the atom is in an "excited state," which is inherently unstable. It's like holding a ball at the top of a hill – it wants to roll back down. This temporary energy boost means the electron won't stay in its elevated position for long. It will eventually return to its original, lower energy level, or even an intermediate one, by releasing the absorbed energy. This release often takes the form of a photon, which is how we get light from excited atoms.

Crucially, excitation is a reversible process. The electron moves up, then it moves down, and the atom returns to its ground state, ready to be excited again. This cyclical nature is key to many light-emitting technologies.

The Atomic Escape Act: What is Ionization?

While excitation involves an electron moving within an atom, ionization takes things a step further. Ionization occurs when an electron receives so much energy that it completely breaks free from the gravitational pull of its atom's nucleus. It's not just moving to a higher rung on the ladder; it's escaping the ladder entirely.

When an electron is ejected from an atom, the atom loses a negative charge. This leaves the atom with an imbalance: it now has more positively charged protons in its nucleus than negatively charged electrons orbiting it. The result is a positively charged particle called a positive ion. The ejected electron becomes a "free electron," no longer bound to any specific atom.

Energy for ionization can come from various sources:

- High-Energy Radiation: Exposure to energetic photons (like UV light, X-rays, or gamma rays) or particles (alpha particles, beta particles) can provide enough energy to knock an electron out of orbit.

- Collisions with Charged Particles: Similar to excitation, collisions can cause ionization, but the energy transfer needs to be much greater. This is a common mechanism in high-temperature gases and plasmas.

- Thermal Energy: In extremely hot environments, atoms move so rapidly and collide with such force that electrons are stripped away, leading to a highly ionized state known as plasma.

Unlike excitation, ionization is generally considered an irreversible process in the immediate sense. Once an electron is removed, it doesn't automatically return to its original atom. The atom's chemical properties are fundamentally altered; it is no longer a neutral atom but a reactive ion. These ions can then attract other free electrons, form new chemical bonds, or undergo further reactions. The presence of ions and free electrons is characteristic of a state of matter called plasma – the fourth state of matter, crucial for technologies like neon signs and plasma light.

Excitation vs. Ionization: Two Paths, Different Outcomes

While both excitation and ionization involve adding energy to an atom and changing its electronic configuration, their outcomes and implications are profoundly different. Understanding these distinctions is crucial for grasping how various light sources and technologies function.

| Feature | Excitation | Ionization |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Electron moves to a higher energy level within atom. | Electron is completely removed from the atom. |

| Resulting Entity | Excited atom/molecule (still neutral). | Positive ion and a free electron. |

| Reversibility | Reversible; electron returns to lower level. | Irreversible (electron doesn't automatically return). |

| Energy Required | Specific, discrete energy "quanta" for jumps. | Higher energy, exceeding the electron's binding energy. |

| Effect on Atom | Temporary change in energy state, potential photon emission. | Permanent change in charge and chemical reactivity. |

| Example | Electron in a fluorescent tube absorbing energy. | Gas atoms in a lightning bolt losing electrons to form plasma. |

| Think of it this way: excitation is like lifting a book from a lower shelf to a higher shelf within the same bookcase. The book is still in the bookcase, just at a different height. Ionization is like throwing the book entirely out of the window – it's gone from the bookcase, creating a new, separate entity (the book outside) and leaving the bookcase changed (now missing a book). |

The Light Show Begins: Photon Emission

The reason excitation and ionization are so critical to understanding light is their direct link to photon emission. A photon, in essence, is a tiny packet of electromagnetic energy – what we commonly call light.

The most common way photons are emitted is through de-excitation. When an electron in an excited state falls back down to a lower energy level, it must release the energy it gained. This excess energy is not simply "lost" but is emitted as a photon.

The Physics of Light and Color

- Energy Match: The energy of the emitted photon precisely matches the difference in energy between the two electron levels involved in the jump.

- Wavelength and Color: The energy of a photon dictates its wavelength, and wavelength determines the color of visible light (or where it falls in the electromagnetic spectrum, such as ultraviolet, infrared, X-ray, etc.).

- Larger energy drops produce higher-energy photons (e.g., blue light, UV light).

- Smaller energy drops produce lower-energy photons (e.g., red light, infrared light).

This principle is why different elements, when excited, emit light of specific, characteristic colors. Each element has a unique arrangement of electron energy levels, leading to a unique set of possible energy jumps and thus a unique "spectral fingerprint" of emitted colors. This is the basis of spectroscopy, a powerful tool used to identify elements in everything from forensic samples to distant galaxies.

Bringing it All Together: Light in Action

Understanding excitation, ionization, and photon emission isn't just an academic exercise; it's the foundation of countless technologies and natural phenomena.

The Everyday Magic of Fluorescent Tubes

Let's revisit the classic fluorescent tube, a perfect example of these processes working in concert, as provided in our ground truth:

- Initial Excitation & Ionization: An electric current is passed through a low-pressure gas (often mercury vapor) inside the tube. This electricity provides energy to the electrons in the gas atoms.

- Collisions and Excitation: These energized electrons collide with the mercury atoms, causing their electrons to jump to higher energy levels (excitation). Some collisions are energetic enough to completely remove electrons, leading to ionization and the formation of a plasma.

- Photon Emission (UV Light): The excited mercury electrons are unstable. When they fall back to their lower energy levels, they release their excess energy primarily as ultraviolet (UV) photons, which are invisible to the human eye.

- Visible Light Conversion: The inside of the fluorescent tube is coated with a phosphor material. This phosphor absorbs the high-energy UV photons.

- Secondary Excitation and Visible Photon Emission: The absorbed UV energy excites the electrons within the phosphor atoms. As these phosphor electrons de-excite, they emit lower-energy photons, which fall within the visible light spectrum – the light we see!

This multi-step process effectively converts invisible UV radiation into the visible light that illuminates our rooms.

Beyond Fluorescents: A World of Light

The same fundamental principles are at play in a vast array of light sources:

- Neon Signs: Electric currents ionize and excite noble gases (like neon, argon, krypton) within glass tubes. When the excited gas atoms de-excite, they emit characteristic colors of light directly (neon emits red, argon with mercury emits blue, etc.). This demonstrates a direct link between the excited state of specific atoms and the color of the light we perceive.

- LEDs (Light-Emitting Diodes): In LEDs, current flows through semiconductor materials. When electrons and "holes" (electron vacancies) recombine, energy is released as photons. The specific semiconductor material determines the energy of the photon and thus the color of the LED.

- Lasers: Lasers rely on a process called "stimulated emission." Atoms are first excited to a higher energy level. Then, a photon of the exact right energy stimulates an excited atom to release another identical photon, creating a cascade of perfectly synchronized light waves.

- Aurora Borealis/Australis: High-energy particles from the sun collide with atoms and molecules in Earth's atmosphere, exciting them. As these atmospheric particles de-excite, they emit photons, creating the breathtaking green, red, and purple lights of the aurora. The color depends on the type of atom (oxygen, nitrogen) and the altitude of the collision.

- Spectroscopy: This scientific technique uses the unique "fingerprints" of emitted or absorbed photons to identify the elemental and molecular composition of substances. By exciting a sample and analyzing the emitted light's spectrum, scientists can determine what it's made of. This is vital in fields from astronomy to environmental monitoring.

- Arc Welding: The intense heat of an electric arc ionizes gases between electrodes, creating a superheated plasma that emits powerful light and heat, used to melt and fuse metals.

Diving Deeper: Nuances and Applications

While the basics are powerful, the world of excitation and ionization has many fascinating layers.

Different Flavors of Excitation

Not all excitation occurs in the same way, and the method can influence the subsequent photon emission:

- Thermal Excitation: When a substance is heated, its atoms and molecules gain kinetic energy. These collisions can excite electrons. This is why hot objects glow (e.g., the red glow of a heating element, the yellow flame of a candle).

- Electrical Excitation: As seen in fluorescent tubes and neon signs, passing an electric current through a gas causes electrons to accelerate and collide with gas atoms, leading to excitation and ionization.

- Photoexcitation: This is excitation specifically caused by the absorption of photons. It's how solar cells work (photons excite electrons to generate current) and how plants perform photosynthesis (photons excite chlorophyll electrons to drive chemical reactions).

- Chemiluminescence: In some chemical reactions, energy is released directly into electrons, exciting them. When these excited electrons de-excite, they emit light without significant heat, as seen in glow sticks.

The Importance of Ionization

While often associated with high-energy or destructive processes (like radiation damage), ionization is also incredibly useful:

- Plasma Technology: From semiconductor manufacturing to fusion research, controlled plasma (ionized gas) is a critical medium. The high reactivity of ions and free electrons makes plasma excellent for etching, coating, and even generating power.

- Mass Spectrometry: This analytical technique ionizes molecules, then separates them based on their mass-to-charge ratio. By analyzing these ions, scientists can identify the components of complex mixtures.

- Radiation Detection: Many radiation detectors work by detecting the ionization events caused by high-energy radiation passing through a material.

- Air Purifiers: Some air purifiers use ionization to charge dust particles, making them stick to collection plates or fall out of the air.

Common Questions and Misconceptions

Is ionization always "bad" or destructive?

Not at all. While high-energy ionizing radiation (like gamma rays) can damage living tissue, ionization is also a vital process in many beneficial technologies. It's fundamental to how fluorescent lights work, how plasma displays create images, and how analytical instruments identify substances. The key is controlling the energy and environment.

Do excited electrons stay excited forever?

No. Excited states are temporary and unstable. Electrons will typically return to lower energy levels almost instantaneously (within nanoseconds), emitting photons in the process. This rapid de-excitation is why light sources appear to glow continuously even though individual electrons are constantly making rapid transitions.

Does all excitation lead to visible light?

No. The photons emitted can span the entire electromagnetic spectrum, from radio waves to X-rays. What we perceive as "light" is only a tiny portion of this spectrum (visible light). Many excited atoms emit UV, infrared, or other forms of electromagnetic radiation, which are invisible to the human eye but have crucial applications.

Can an atom be excited and ionized at the same time?

Yes. It's possible for an atom to lose one or more electrons (ionize) and still have its remaining electrons become excited to higher energy levels. This often occurs in high-energy environments like plasmas, where ions themselves can be further excited or even multiply ionized (lose multiple electrons).

The Invisible Architects of Light

From the most ancient starlight reaching our eyes to the latest generation of quantum computing, the fundamental interactions of excitation, ionization, and photon emission are the invisible architects behind the light that shapes our perception and powers our world. They are the elegant principles that govern how energy is absorbed, transformed, and ultimately released as the vibrant spectrum we call light.

Understanding these processes doesn't just demystify how your light bulb works; it opens a window into the core mechanics of the universe, revealing the dance of electrons that makes all visible phenomena possible. It’s a powerful reminder that even the most complex displays of light are rooted in the simple, yet profound, behavior of subatomic particles.